Hidden Epidemic of Legal Failure in Developing Nations

Hidden Epidemic of Legal Failure in Developing Nations

By Khurram Niaz

The court system in many developing countries bears the unresolved burden of colonialism. The strict and antiquated legal systems that were frequently passed down from prior imperial rulers are not appropriate for the demands of modern, democratic society. Little significant reform has taken place, despite the expectation that what was once a tool of control will now provide protection. Deteriorating infrastructure exacerbates this structural inertia: in certain regions, courts run without electricity, case papers are left to fester in unprotected chambers, and hearings drag on for years because of massive backlogs.

There is considerably more dysfunction in underserved and rural communities. Vacancies in the judiciary remain unfilled for months. When someone is appointed, it’s usually an underqualified person with a tons of cases and little institutional assistance. In these areas, residents experience indifference, confusion, and delay rather than justice or clarity. Justice turns into a mirage that is never realized, keeping the oppressed in cycles of hopelessness and silence.

Developing Nations

Justice is not only delayed but also completely unaffordable for the impoverished. In many nations, most residents cannot afford the luxury of legal representation. When they do exist, public defenders are usually undertrained and overburdened. An unbreakable barrier is created by court fees, travel expenses, and even unofficial bribes. In reality, only the elite have access to the legal system. Because they are unable to pay bail, those accused of minor offences may be imprisoned for months or even years. A defendant’s destiny is frequently determined by poverty rather than guilt. Another obstacle is legal literacy: millions of people go to trial without knowing the laws they are allegedly violating, without advocate, interpretation, or direction.

This ignorance and illiteracy create a perilous silence. People skip court dates they were not adequately informed of, sign confessions they are unable to understand, and lose cases before they ever start. Justice is biassed in such a setting in favor of the knowledgeable, well-connected, and most importantly, the wealthy.

As the public’s initial interaction with the legal system, police far too often inspire dread rather than confidence. Coercion taints this meeting in many impoverished countries. It is still alarmingly common for confessions to be obtained under pressure, particularly in high-profile instances. Vulnerable suspects are frequently beaten to submission behind shut interrogation room doors, and their testimonies are then admitted into evidence as “voluntary.”.

That is not the end of the manipulation. Crime scenes are altered, records disappear, witnesses are coerced or bought off, and evidence is falsified. When there is little oversight and even less responsibility, resolving cases takes precedence over finding the truth. Justice can be a nightmare for people who cannot afford bribes. Law becomes a commodity for those who can afford it.

The goal of policing in this setting is to control public opinion rather than uphold the rule of law, frequently at the expense of justice, equity, and fundamental human decency.

Courtrooms become tools of repression rather than havens of justice in politically unstable regimes. Laws like anti-terror or blasphemy regulations that were first designed to maintain order are regularly used as weapons to stifle dissent, target minorities, and stifle the press. Speaking up against authority, exposing corruption, or advocating for reform might put one in a legal trap that is intended to punish rather than to uncover the truth.

Most of the time, this politicization begins at the top. In the manipulation of judicial selections by ruling parties, loyalty is prioritized over ability. When meritocracy is compromised for political ends, the judiciary’s independence and legitimacy are threatened. The unseen hand of military establishments or intelligence services frequently determines the result of high-stakes cases, especially those involving political leaders or national security.

At the same time, corruption is made possible by the substandard living conditions of judges and court employees. They are vulnerable to outside influence because of their low pay and scant perks. The elite, business interests, and political players take advantage of this weakness to slant rulings in their favor. Justice turns into a transaction, accessible to those in positions of power and inaccessible to others.

When Justice Serves Power, Not People:

There comes a time when injustice ceases to be an accident and starts to happen on purpose. It is a threshold that the system has surpassed in many emerging nations. Previously regarded as emblems of justice, courts now frequently reflect the wishes of the powerful rather than the rule of law. It is obvious that justice is now planned rather than blind due to manipulated decisions, staged trials, and systematic breaches of human rights.

Public response becomes both predictable and dangerous as this fact gets ingrained. People look for alternatives when they lose faith in the legal system. The gaps are filled by mob justice, tribal councils, and religious courts, which provide quick but frequently harsh decisions. These unofficial procedures completely circumvent due process. Public humiliation, rival court systems, and lynchings take the place of declining trust in state institutions.

This decline in judicial legitimacy is a watershed moment for society as a whole, not just the legal system. The basis of social trust starts to erode when justice is no longer a shared civic value rather fear, chaos, and fragmentation take its place.

A second trauma that women may experience in the courtroom is legal humiliation. There is rarely any urgency or empathy shown to survivors of rape, domestic abuse, or inheritance disputes. Instead, offenders profit from a system that is unable to question long-standing patriarchal norms, while they are frequently scrutinized for their actions, attire, or personalities. Cultural bias and outdated legislation make matters worse. Domestic violence is treated as a personal matter in certain places, while marital rape is not considered a crime in others. Daughters and widows are frequently deprived of their legitimate interests by inheritance rules, which are justified by tradition.

The atmosphere might remain hostile even after a case goes to trial. Women are often dissuaded from seeking justice, and victim-blaming enquiries are commonplace. Too frequently, both the institutions designed to protect women and their abusers muffle their voices in a legal system that was created by and for men.

Children are also victims of this flawed system. Juveniles are frequently tried as adults in overcrowded courts and disorderly jails, depriving them of age-appropriate protections. Children who are homeless, illegal, or orphaned are easy targets; they are picked up, falsely charged, and imprisoned without proof just to meet quotas.

These kids are subjected to torture, exploitation, and brainwashing in detention centers rather than rehabilitation. In a system that criminalizes their existence rather than providing assistance, their trauma gets worse every day. The legal system frequently decides their fate before they even become adults, instead of giving them another chance.

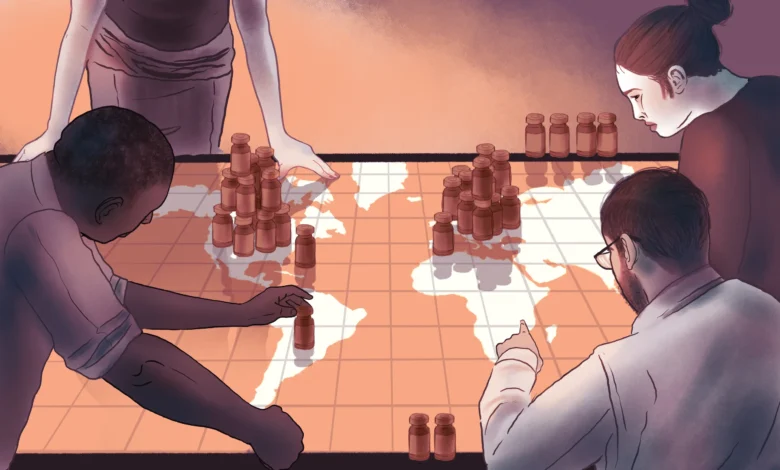

There are many disclaimers attached to international concern for justice in poor countries. Selective outrage is brought on by news stories or political opportunities. If the partnership suits geopolitical or economic objectives, Western countries often support authoritarian governments with poor legal records. Promises of economic agreements, military access, or regional stability overshadow worries about wrongful detentions or sham trials.

Global human rights activism loses credibility as a result of these unequal standards. When transgressions are condemned in one nation but disregarded in another, justice begins to manifest as a political tool rather than a universal ideal. People who are stuck in broken systems feel betrayed by their governments and the international community as a result of this contradiction.

Nevertheless, despite this malfunction, resistance sparks still flicker. The void is being filled by civil society organizations, who offer free legal aid, keep tabs on court proceedings, and promote reform. Courageous attorneys, reporters, and activists continue to hold unfair systems responsible all across the world, frequently at considerable personal danger.

Technology is being used by youth-led activism to raise knowledge of the law, demand accountability, and document violations. A new generation is taking back justice through digital campaigns and mobile legal clinics. These grassroots initiatives are rebuilding, not only responding.

There is a growing call for systemic change, including depoliticized courts, merit-based judicial nominations, and funding for accessible and equitable legal institutions. The seeds of transformation are firmly sown, but the path ahead is lengthy. Justice need not be permanently denied, even if it is long overdue.

Khurram Niaz

Khurramniaz929@outlook.com

Developing Nations

Developing Nations